A few years ago, as life emerged from the ravages of the COVID pandemic in sometimes new forms, I was asked to speak to a collection of large employers at an online event organised by the Harvard Learning Innovations Laboratory (LILA). The purpose of the event was to explore the role of place in work. In other words, to consider the workplace as a particular species of place. What was obviously on the minds of the employers, who included Apple and Meta, among others, was that their employees had gotten used to working from home during lockdowns and were reluctant to return to the workplace. The employers both wanted to understand this, and, in some cases, to find ways to encourage their employees to return to the workplace. The reasons for this were articulated differently by different people, but mostly boiled down to the need to ensure a workplace culture and identity that they believed was best achieved by having a shared space that employees habituated and identified with. In this respect they were thinking of workplaces in very similar ways to how we might think of nation-states as identity-giving places, or, indeed, our own homes as sites that give us a sense of who we are. Historically, one of the primary roles of place as a centre of meaning and field of care has been to nurture a sense of belonging and identity. Workplaces are no different. As well as being functional spaces of labour, and spaces of surveillance and control, they have long been considered as sites where feelings of pride and belonging can be evoked.

At the Harvard event the gathered employers did not seem primarily concerned with productivity. Indeed, research suggests that productivity, as well as employee wellbeing, has in many cases improved with home working and flexible hybrid working arrangements.[1] They appeared to be mostly concerned with less tangible senses of belonging and company spirit. They were hoping that a cultural geographer might be able to help.

When I received the invitation, I was immediately reminded of the story of General Electric (GE) and the 2016 planned relocation of their headquarters from a nondescript location in suburban Connecticut to the newly developing Seaport area of Boston. A press release read:

“GE aspires to be the most competitive company in the world,” said GE Chairman and CEO Jeff Immelt. “Today, GE is a $130 billion high-tech global industrial company, one that is leading the digital transformation of industry. We want to be at the center of an ecosystem that shares our aspirations. Greater Boston is home to 55 colleges and universities. Massachusetts spends more on research & development than any other region in the world, and Boston attracts a diverse, technologically-fluent workforce focused on solving challenges for the world. We are excited to bring our headquarters to this dynamic and creative city.”

(GE Press release)

Justin Fox, in Bloomberg News wrote:

“...this move seems great. An office on the waterfront near great restaurants, museums, tech startups and transit stops in Boston sounds a lot more appealing than one surrounded by lawns and parking lots in suburban Connecticut.”

Justin Fox (Bloomberg News, January 13th, 2016)[2]

Clearly key elements of place were in play in GE’s decision. The relative location of a new HQ surrounded by universities, restaurants, transit, museums etc. is both functionally useful (GE was moving from old fashioned industry into the glamourous world of “tech”) and geographically rich in other ways.

While location is clearly important to businesses – they must have easy access to capital, labour, and whatever materials they require – locales are too. It is not just where a workplace is but what kind of place it is both inside and outside. Locale refers to the physical and social context within which social relations unfold. Locale refers, in one sense, to the landscape of a place - its physical manifestation as a unique assemblage of buildings, parks, roads, infrastructure. Locale also refers to place as a setting for particular practices that mark it out from other places. These include the everyday practices of work, education and reproduction amongst others. We often know a place, in some sense, as a locale – a unique combination of things and practices within which life unfolds. Thinking about workplaces thus involves what the place of work is actually like – layout, decoration, provision of coffee, furniture etc. It also involves the locale that surrounds it. Is it in a business park surrounded by lawns and parking lots – or is it in a richly textured kind of place? A city.

Sense of place refers to the subjective side of place – the meanings that attach to it either individually or collectively. What meanings does a workplace have for employees? Part of the problem with the Connecticut setting for GE was its soullessness – there was no there there. Any sense of place it had was negative – a kind of placelessness. Boston seemed to be a real place.

The sense of place in suburban Fairfield, Connecticut vs the sense of place in a newly developing waterfront in central city area was an important factor in the decision. In one place you had the typical suburban office landscape with not much more than anonymous office blocks and surrounding parking lots while in the other you would have a city and all that comes with it.

The kinds of companies present at the Harvard workshop are known for having both spectacular buildings and innovative internal formats. These are the kinds of companies that provide beanbags and chill-out zones. It is a million miles from Ford’s assembly line or the kind of functional open plan office with lines of workers at desks with typewriters and phones – such as that featured in Billy Wilder’s 1960s movie, The Apartment.

It is not surprising that the design of workplace interiors has changed as it is the material structure – or locale – of a workplace that is the easiest to transform. Just as placemakers more generally fixate on physical and aesthetic transformations, so workplace innovators can most easily think in terms of hot-desks, beanbags, and chill-out zones. Whatever the question is, design seems to be the answer.

One problem with these approaches is that workplaces are not sealed off from the world around them. For workers, a workplace forms part of an ecosystem of places that include home, and spaces of leisure, education, care, and the all-important “third places” of sociality. A workplace is part of a wider geography – nested within other places. So rather than just focusing on the interior of a workplace, employers need to think about how their places contribute to the communities around them. Are they fortresses turned in on themselves in exclusionary ways or are they part of communities, welcoming connections to others who inhabit their neighorhoods and share their spaces?

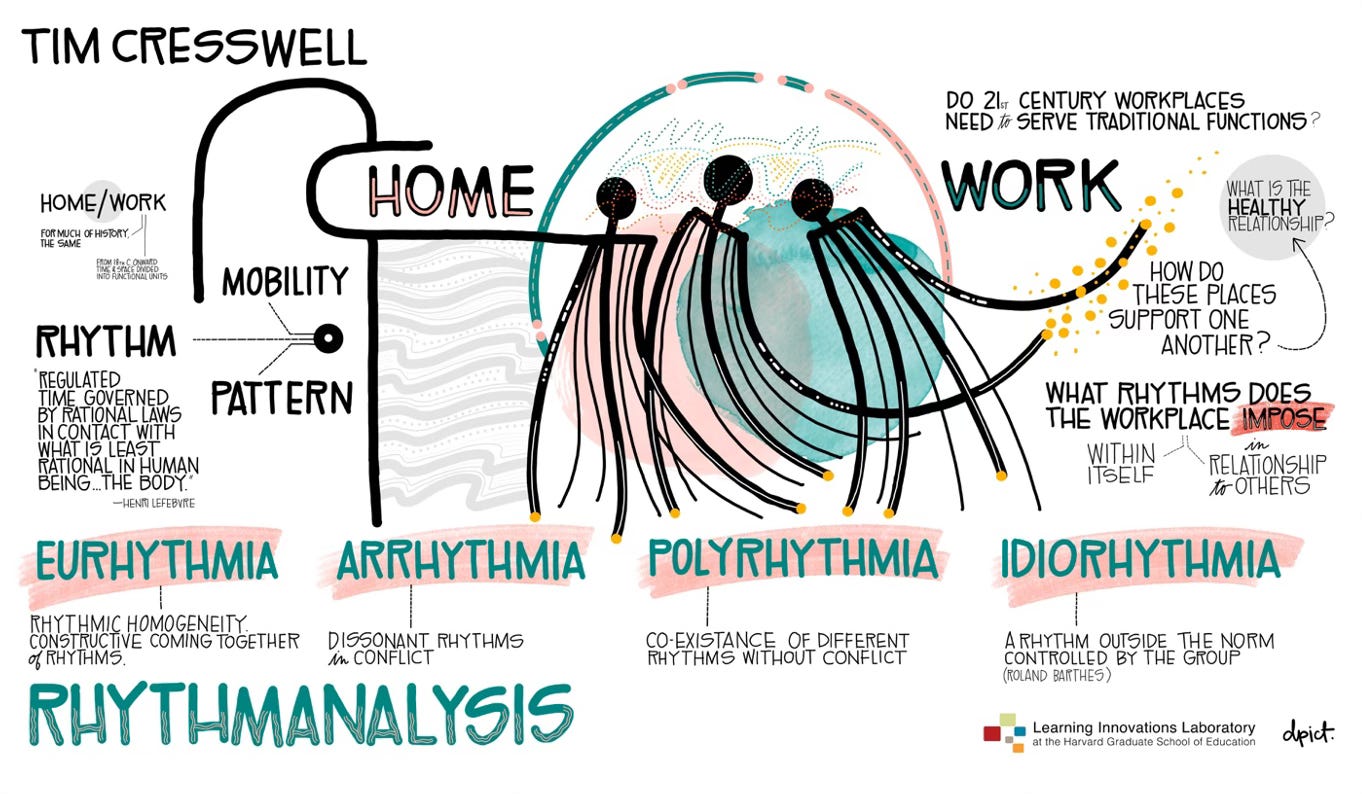

Workplaces form part of the rhythm of life for workers. They have long been a key part of structuring everyday life as the difference between homeplace and workplace emerged along with the notion of the eight-hour working day. This was one of the key demands of labour unions marching for “eight hours for work, eight hours of rest, and eight hours for what we will”. More important than beanbags and coffee machines (though they are nice), are how employers recognise the needs for work-life balance, the importance of time for child-rearing and family life, and the ability of workers to easily move between the spaces of their lives. Employers should be asking how they fit into the ecology of everyday rhythms of time and space in ways that foreground the wellbeing of employees. In other words, they should be asking what rhythm their workplaces impose and how much freedom employees have in generating their own rhythms of life. This means recognising that workplaces (like all places) are connected to other places.

In 2022, as everyday life returned to normal following COVID, the planned relocation of GE to Seaport was dramatically scaled back. As WBUR reported:

“GE says it plans to keep its HQ in Boston, but the 100,000-square-foot Seaport property was more than it ever ended up needing. While they had planned to bring 800 jobs to the new HQ, "fewer than 200 people are based there now and many only come in on a part-time basis," according to The Boston Globe. It's unclear how many people GE plans to keep at the new location.” (WBUR, October 19th, 2022)

While GE was struggling with its business, it was also the case that workers were now not required to be at the planned glossy campus. Part-time presence was now normal. Perhaps the nature of the workplace, at least for relatively secure, well-paid employees in knowledge and tech industries, is fundamentally changing post-COVID. The presence of these employees at the LILA workshop was partly a recognition of new realities, and partly an attempt to resist them.

Below are the lovely images produced by LILA based on the two workshops I gave there.

[1] https://www.theguardian.com/business/article/2024/jun/16/hybrid-working-makes-employees-happier-healthier-and-more-productive-study-shows

[2] https://www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2016-01-13/general-electric-says-goodbye-to-the-suburbs?embedded-checkout=true

Enjoyed this piece Tim! Great point about employers asking how much freedom employees have in generating their own rhythms of life, at the end of the day most of us just want autonomy.

Hi Tim:

Interesting piece. The visual materials are great. I will use in my geographic research class sometime in the future. Note that GE was in Fairfield, CT not Fairfax.